The wrong order

Tim, my brother, died over twenty years ago. Some of my earliest memories are of him writing poetry. Before he died he had a plan to get some of his poems together for publication. But he didn't have time. Between diagnosis and death he had only a few months. And morphine and suffering kept him busy.

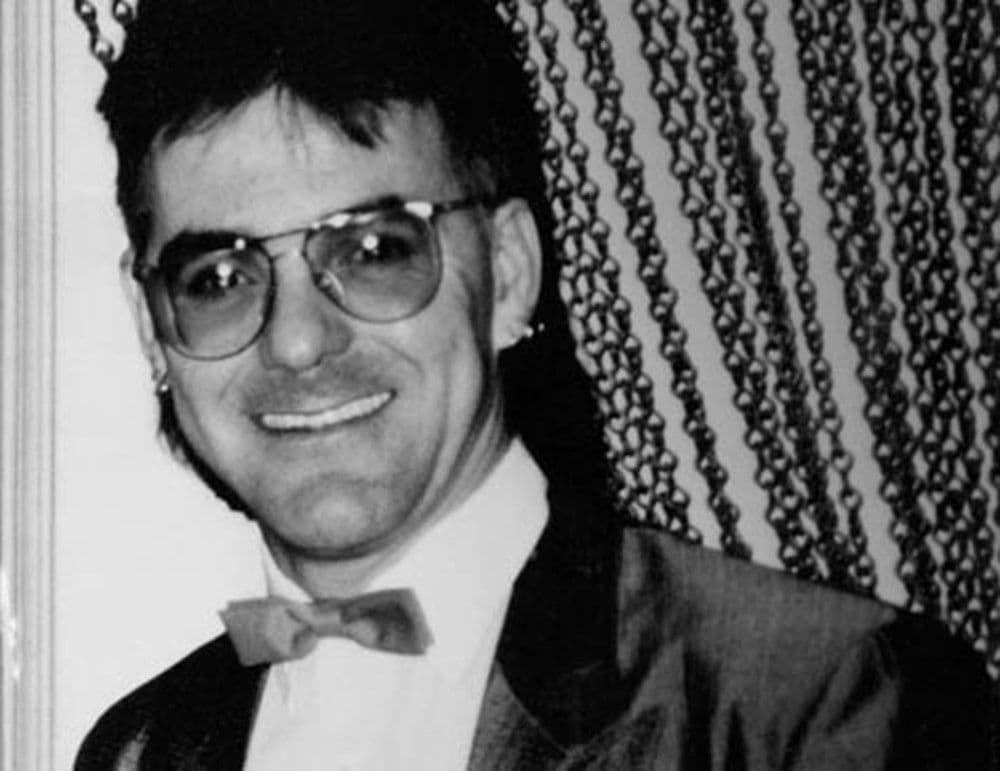

Tim Walsh

Tim Passes, Dark Mofo 2014

After he died I set about locating all the worthwhile material I could. But, to my continuing shame, I managed to lose a folder which contained a number of bleak, beautiful poetic capitulations to his condition. His cancer didn't come out of the blue. He had a congenital condition, choledocal cysts, which had been operated on when he was just six months old. The result was arguably positive, death was deferred thirty-three years, but through those years Tim endured severe, chronic pain.

The site of this type of surgery, it turns out, often becomes inflamed, and that led to his symptoms, and that led to his cancer. For some reason nobody told him that might happen. He, nevertheless, often speculated that he would die young. He didn't think his body could sustain the repeated insults. I know where I left the folder. On the stereo cabinet. And I know what was playing when I put it down. It was Paul Simon's ‘Most Peculiar Man’.

And all people said, what a shame that he is dead.

But wasn't he a most peculiar man?

I went to get the folder the next day, or the day after that, and it wasn't there. It hasn't been there, or anywhere else as far as I can determine, for those twenty years. So, just like Tim, that time has passed. There won't be a book of Tim's poetry. I only have a few poems left.

Forty years ago.

Tim was a little older than me. He read widely, mainly poetry: Shelley, Shakespeare, Betjeman, Byron, Tennyson, Masefield, Hopkins, Wordsworth, Whitman. And because I didn't know any better I read them too. He taught me stuff I didn't want to know then, but am very grateful for now. He showed me how to write amusing little ditties. This one he wrote when we were still children.

I wrote a simple poem.

A simple poem but mine.

And the words on every second line

Always seemed to rhyme.

And it parted in the middle.

Two verses my poem had,

But it finished on the eighth line,

And that kind of makes me sad.

He taught me about iambs, the stresses on every second syllable that Shakespeare used to astonishing effect. And he taught me about enjambment, running a sentence over the end of a poetic line, used to best effect with rhymes at the line breaks. Thus I wrote:

Playing with some stressful iambs

The line ran out before I could

Finish. I asked myself what would

Shakespeare do? And then I knew.

A ploy poets call enjamb-

Ment. When I write myself into

A corner. I escape just like Ham-

Let. That's as tricky as Harry Hou-

Dini.

Two years ago.

As a surprise for my fiftieth birthday, some friends commissioned Dean Stevenson to set a couple of Tim's poems to music, and to play them at the party. It went well. One poem he chose Tim had written for my twenty-first birthday. He had been in hospital having another round of surgery, and was mindful of his mortality. Thus it began:

Time passes, and we being mortal, think of death.

The songs went so well, in fact, that Dean asked for more poems. But there are no more, he had already been given the eight that I know of. Those eight were, apparently, enough. Enough for this concert, at least.

Twelve years ago.

Mum died in 2001. Every night between Tim's demise and hers she read a poem before she went to sleep. James, Tim's son, wrote in the note he sent to Dean when they colluded on my birthday present, that ‘Dad... composed this for my grandmother Myra, to help her feel some joy in his memory’.

When thine eyes have lost their soft dream shine

At pass of years and loss of time

And you are old and grey and full of sleep

When your heart is sad and your soul is deep

Stop. Reflect. Wipe away your tears

And think of the joys of bygone years

Think happiness. Friends and laughing lovers

Think of good times, come, think of others

But should no joy come from your past time

Take down this poem and read its rhyme

Hold it tender, close, and near to thee

Think of one friend. Think of me.

Twenty-two years ago.

When Tim went into hospital he was already dying, but we didn't know. They opened him up, confident they could fix him. When a mooted four-hour operation took fifteen minutes we knew something was wrong.

So all the interventions became palliative. A nurse was assigned to show Tim how to use oral morphine. Tim said, ‘I know all about that, I had to administer it to my son, Billy’. Billy was born with disabilities, and dead at eight months. Dad said, ‘We die in the wrong order in this family’. Dad was already seventy-five, but destined to live another eighteen years. They sent Tim home.

At home Tim played his girlfriend and me a song, ‘Stuff and Nonsense’ by Split Enz. The chorus goes:

And you know that I love you

Here and now, not forever.

I can give you the present

I don't know about the future

That's all stuff and nonsense.

Dean Stevenson and the Arco Set Orchestra will perform Tim Passes at Dark Mofo on Thursday June 12, 7pm at the Odeon Theatre.