Introducing Sunday

These are Gros Michel bananas. Unless you've carefully sampled exotic fruit varieties in Thailand, or are over seventy, you don't know what they taste like. Gros Michel comprised the bulk of all bananas sold in the world until the 1950s, when a fungus almost wiped them out. Now we mostly eat Cavendish bananas, but they are also threatened by disease. Banana varieties are clones. A single variety has no genetic diversity, and can thus be threatened by a single disease or parasitic species.

Komodo dragon

This is a pathenogenic ('virgin creation') lizard, a Komodo Dragon. It is non-obligate, which means that individuals of this species can also reproduce sexually. In the short term pathenogenesis offers significant advantages. For the Dragons, who are island dwellers, it seems a great way for an individual to start a new population on its own. Obligate pathenogenic species have the significant advantage of not having to locate mates. But obligate pathenogenic species don't last long. They suffer from the ravages of rapidly evolving parasites, and they don't have the genetic diversity to express a sufficient range of phenotypes to respond to changing environmental conditions or inter-species competition. Asexual reproduction is a dead end. Fortunately, no man is a banana. And no little girl is a Gros Michel.

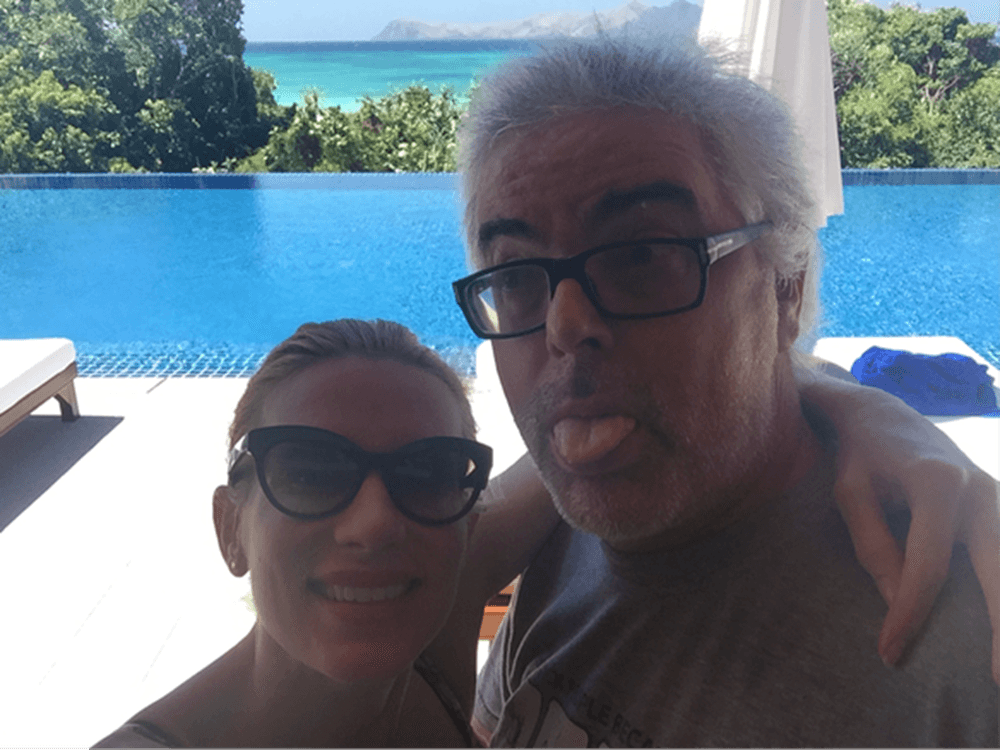

David and Kirsha

These are two examples of a mammalian species that employs only sexual reproduction (despite one or two outlier claims). Unlike obligate pathenogens they have engaged in mate location. They did that because searching for a mate is fun. It's fun because if it wasn't they wouldn't do it, and they wouldn't pair-bond and they wouldn't breed and they wouldn't love and they wouldn't care enough to provide enough care, and they wouldn't have their children grow up to love and care for their children and their species wouldn't abide. These two individuals, having been assigned (and in one case re-assigned) names due to social convention, are known as Kirsha and David.

So Kirsha and David, each found a lover, found each-other, became bound to each-other, became mutual care-givers, and made another. And as members of a species within which individuals possess self-awareness, viewpoints can be expressed. Such viewpoints are typically congruent with biologically normative exigencies, but are expressed as if the social domain is dominant. This engenders a first-person narrative style.

Sunday

This is our freshly minted little girl. The physical manifestation of our evolutionary drives. We think she is beautiful, but we would, wouldn't we? Evolution sees to that. And evolution, often through concealed agency, sees to it that we express, or attempt to enhance, our social status by communicating our great good fortune at having a healthy by-product of our pair-bonding, and of our love. I could shout it from the rafters, or hand out cigars, but a blog should do the job.

Heide Museum

This is Heide Museum, near Melbourne. One of the reasons Kirsha and I have experienced a productive pair-bonding is that our biologically expressed but socially mediated interests are aligned. Sharing interests allows one to select appropriate mates, but it also allows the signaling of appropriate bonding mechanisms. If I liked hotting-up cars, say Toranas, then conspicuous displays of my Torana prowess, say a donut demonstration, would reduce the amount of resource expended on testing inappropriate mates with inappropriate interests. But I like art and, using my collection and the construction of a museum, I gave off signals to which Kirsha was apparently receptive. And so I took her to Heide. I saw, in Heide, the birth-pangs of Australian modernism (presently an uncomfortable metaphor). Kirsha saw in it a kindred spirit to her art garden projects – in New Orleans and now in Hobart. John and Sunday Reed made Heide, and thus might been inadvertently complicit in the tenuous chain making our relationship. And, of reeds – 'Man', said Blaise Pascal, 'Is but a reed, the most feeble thing in nature, but he is a thinking reed'. That may be so, but our joyful little bundle of biology is female, not yet thinking so much, but already employing her natural gifts to elicit our love, to prevail on us to preserve her from breaking in the breeze. Our reed will be called Sunday. Never shall be Sunday too far away.